Spinster

Why Jane Austen Never Married

Why Jane Austen Never Married

Once upon a time the famous writer known as Jane Austen decided not to get married. Not a vital issue in this day and age perhaps, but Austen was one of the finest novelists of the English language and all her heroines end up safely in the arms of a husband by the final chapter. Austen was a highly intelligent woman and she wasn’t bad looking, so why did things turn out so differently in her own life? We know that she received a marriage proposal from a gentleman named Harris Bigg-Wither toward the end of 1802, that she accepted, and that the following morning she told Harris that she had changed her mind. Why?

Many have speculated about Austen’s reasons but no one knows for sure since she never wrote about them. Or did she? At the time, Jane was 27, Harris 21 and about to become a clergyman. Perhaps his age or his profession was an issue? He was a family friend from the neighborhood she loved, and his sisters were close friends -- it could have been a good match, given her choices. But she turned him down flat and one wonders whether there were other factors at work. In 1995 allegations surfaced that Austen was a lesbian and involved in an incestuous relationship with her older sister Cassandra. While this is a colorful theory, it arose out of a misunderstanding of an academic paper on Austen, and it points instead to our own culture’s thirst for scandalous sexual fables. It points to exotic explanations tailored to suit a sexual or political agenda. Perhaps it never occurred to people that in those days sisters often shared a bed? Hollywood and the British film and television industry also leapt into the fray with a seemingly endless stream of adaptations of most of her novels, even Northanger Abbey, as well as sequels and spin-offs. Austen's fans have written handbooks, cookbooks, fan fiction and other retellings... Melodramatic as all this sounds, the most interesting question that remains is: Why did Austen decide against marrying Harris?

The year was 1802, the dawning of a new century and England was at war. Across the “English” Channel, Bonaparte had Europe on the run and Trafalgar and Austerlitz were just around the corner. In Germany Romanticism was awakening a national identity. Goethe was at home in Weimar working on Faust while Beethoven was in Vienna writing the anguished diary entry known as the Heiligenstadt Testament in which he comes to terms with his increasing deafness and the power of music to move the soul. Ireland was restive after being forcibly united with Britain and the first steamship was traversing the Clyde in Scotland. In the Americas Jefferson was President of a rapidly expanding and newly independent United States. John Wilkes and Casanova were dead; George Sand would not be born until 1804 and Charlotte Brontë would not be born until 1816, the year before Austen died. Austen herself had completed several novels already but the first would not be published until 1811. So… why did she never marry?

“SHE HAS NOT MET THE RIGHT PERSON”

Cassandra and Jane Austen were seeing out the end of the year 1802. They had been shuttling around the various members of their extended family, scattered along the south coast of England. If Napoleon had ever wished to invade, he would have run into the Austen women ready to repel the French boarders. The sisters found themselves, after a time, back at their old family home at Steventon in Hampshire (shown up top, although it's a rebuild from 1823); their oldest brother James and his wife Mary were living there. Cassandra and Jane took the opportunity to visit their old friends the Bigg-Withers at nearby Manydown. Out of the blue, it seemed, Harris Bigg-Wither made his marriage proposal to Jane. She accepted with surprising speed, but the next morning informed him that she could not go through with it.

This startling announcement turned things upside down. Jane and Cassandra took the Bigg-Wither carriage back to the old house as fast as it would go, accompanied by three distraught Bigg sisters, and there followed an emotional goodbye in the hallway. Jane and Cassandra demanded that their brother James take them back to Bath that very morning although they knew this would mean he would miss his preaching the next day. Some things are more important than keeping the local congregation of harpies happy and so a substitute was quickly found. They were not about to stay in that neighborhood a day longer with Harris on the loose.

Cassandra reflected on this turn of events as they settled back into the slow routines of Bath. She had opposed the match herself though she confessed she was no wiser on why Jane had changed her mind. More to the point, she wondered why Jane said yes in the first place. There were distinct advantages of course. For one thing, Harris was a gentleman of good character, he had solid connections, he owned property and he had a worthy position in life. By marrying him, Jane would no longer be a burden on their father’s limited financial resources and she would, if anything, have been able to look after their parents in their declining years, as well as Cassandra if she remained unmarried, as seemed inevitable. Jane would have run a sizable household, had children and enjoyed the genteel country life in a location she always loved. In other words, when she changed her mind she knew the risks. For when her father died, they, along with her mother, would be very poorly off. Of course there was always the possibility of a second chance but who can say where Fate will take us?

In Cassandra’s view, the institution of marriage was changing to accommodate radical new ideas like Love, Friendship, and Passion, but it was still essentially a business arrangement. There was nothing truly wrong with that but it did make it harder to satisfy the romantics among them, in which Cassandra included herself. The right person was supposed to have property and a title and, once married, if husbands wanted to satisfy their more basic urges, they were supposed to go to mistresses or prostitutes. It was not a wife’s responsibility apparently. Unless they were clergymen of course. Harris would have been a good choice from that point of view – he would have been faithful. However, he had a stammer, a mean temper, he was a bit reclusive and he was not especially good looking and his health was poor. All right, that is a lot of negatives. The fact is, Jane was not in love with him. “Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without Affection,” she wrote to one of her nieces.

There is no doubt that Jane knew what Passion was. The previous year she had met a young man whom Cassandra believed had touched Jane’s heart. This event had taken place over several weeks in the summer at the beach. He was charming and handsome and Cassandra felt sure that he had fallen in love with Jane. “I believe that, if Jane ever loved, it was this unnamed gentleman; but the acquaintance had been short, and I am unable to say whether her feelings were of such a nature as to affect her happiness.” Cassandra recalled he too was a clergyman and his brother was a doctor or a naval officer. Unfortunately, a marriage proposal never came and the two families parted with the expectation of meeting again soon. Instead, they received a letter from his brother saying he had died suddenly. This certainly leaves room for speculation. Was Cassandra imagining there was more to the relationship than there was? Had he really died or was this an excuse to extricate him from commitments he may have made unwisely to Jane? Whatever the explanation, we will never know, but it is fair to assume that Jane did know what passion was and Harris Bigg-Wither wasn’t it.

No woman should ever trust that she will find Love after marriage if it isn’t there in the first place. Sadly, most young men and women rationalize to themselves why they have ended up married to someone they do not love and Cassandra for one had decided she would rather avoid this foolishness. Her Father and Mother had tried to marry her off of course. They had moved to Bath the previous year for that very reason and Cassandra knew they quietly entertained the noble idea of finding husbands for their wayward daughters. Cassandra and Jane did not enjoy letting their parents down. They were both in their late twenties and, yes, they were still available! Unfortunately Bath had been rather short on eligible young men this year and the sisters had had to face the fact that they were not the best catch in town. They had very little dowry and the few young men who had called on them seem to be unnerved by their own lack of financial resources. Singularly lacking in drive, they would never win any young lady of worth. Perhaps it was just a sign of the times? All the attractive young men were either serving in the military, or married off already, or they were as flaky as pastries.

“TEMPERAMENTALLY UNSUITED TO MARRIAGE”

In Manydown, Hampshire, Harris Bigg-Wither, the rejected suitor, had his own reasons for being disappointed. Many years later, in reflecting on how he had almost married Miss Austen, he might have taken consolation from the fact that she became a cynical old maid. This was not a criticism really, at least not to Harris, for old maids ran the country in their formidable and quiet way and remaining single was a perfectly acceptable lifestyle choice. But there were other reasons why he felt relieved at his narrow escape.

Harris had made Jane a realistic and practical offer of marriage and she had refused. He supposed this was because she thought she could do better and that it was he who was temperamentally unsuited to marriage. Yet it was she who suffered from a permanent distemper toward the entire enterprise. After her death he was privileged to lay eyes on some of her old correspondence and had stumbled across the following: “So Miss B. is actually married, but I have never seen it in the papers; and one may as well be single if the wedding is not to be in print.” Was she serious? In another letter, she had written, “Mrs. Hall, of Sherborne, was brought to bed yesterday of a dead child, some weeks before she expected, owing to a fright. I suppose she happened unawares to look at her husband.”

This was pretty shocking! He had tried to read her other novels to discover further proof of this dark view of life, but he could not say for sure what she was saying. The fact that she did not deal with marriage or sex, but rather the prelude to the both of them, proved how little she knew about them. Not that he felt resentful, but the more he thought about it, the more he felt he had narrowly escaped a life of torment, for this old maid had a vicious sense of humor. He had dropped this offer of marriage in her lap, and she had had the opportunity of approaching it from a rational as well as an emotional point of view. She was not forced into it. Perhaps he was not the ideal marriage prospect but there was no threat of sexual intimidation or sexual desire hanging heavy in the air between them. He recalled the manner in which she damned every remotely passionate encounter in her novels, and the marriages she depicted were even more awful. He concluded that marriage simply did not interest her personally and that she preferred women’s company. Was he being unfair? He didn’t think so.

Frankly, Miss Austen could be terrifying. He knew she could be prickly, that she did not always respect her mother as she should, and he had heard she was cruel toward her nieces. Imagine if she had taken it out on him? Harris would never care to be one of those people who gossiped about others, but he wondered, if they had married, whether their first year would have been filled with visions of her coming after him with a carving knife? Too Gothic? In his mind the root of all this was the constant battle between the sexes. Miss Austen liked to point out to him that it was the men who made decisions about women’s lives and how marriage was tied up with money and property and class. He did not accept her view that he was conservative politically and snobbish socially. He saw things for how they were. The country gentry to which they belonged – really the landowning class of England – were Tory in their political beliefs, and this was the bedrock on which England’s stability rested. There would be no “French” Revolution here. Harris thought women should stay out of politics, and the most honorable profession for someone such as herself was to be good a wife to a clergyman or a lawyer or an officer in the army or navy, like Miss Austen’s own brothers. It was also clear to him now that Miss Austen did not like the prospect of having children. Since those events in 1802, he had gone on to marry, and Harris and his wife planned on having as many children as the Good Lord would grant them. He could say with certainty that Miss Austen would never have been very successful raising 10 children – as he and his wife would be.

Harris knew that Miss Austen had tried to keep the world from knowing she was a novelist but word had leaked out somewhat. What a waste of time it was writing such books! Harris did not think Miss Austen accurately captured their lives. The novels were stuffy; they lacked any manly virtues. Every scene seemed to take place in the drawing room and never progressed to the bedroom (which was fine with him) or even outside the four walls. Harris himself preferred robust adventures about the great missionaries in Africa. Miss Charlotte Brontë had Miss Austen down right: “I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses,” she once wrote to a friend. Miss Brontë was a true Romantic of course; she demanded some Passion in her reading. Harris could see that Brontë despised Austen and that she knew how she could have improved on these novels, retelling them through first person narration and injecting some real emotion. Other writers agreed. Mr. Anthony Trollope criticized Miss Austen’s characters’ restraint and lack of passion, for this “robs the reader of much of the charm which he has promised himself,” and Mr. Henry James wrote that her women were all “Small and second-rate minds.” Miss Austen was simply incapable of the deeper and nobler insights into human nature, especially in her men characters. She was just too cynical. D.H. Lawrence, whose books would otherwise have disgusted Harris, called her “an old maid, unpleasant and snobbish,” while Somerset Maugham remarked that she was “the daughter of a rather dull and perfectly respectable father, a clergyman, and a rather silly mother. How did she come to write Pride and Prejudice? The whole thing is a mystery.” Harris agreed.

“SPINSTER”

Jane Austen sat at the desk in the living room of the family home in Bath to do her writing, working quietly, methodically. Publicly she was not known as a writer, merely an unmarried old maid, and although she was not expecting anyone in particular to come through the door, it was still too early to let others outside the family know of their little secret. And so she scribbled away on her sheets of paper and hid them every time someone came for a visit. She could always pull her letters to the top if anyone became suspicious.

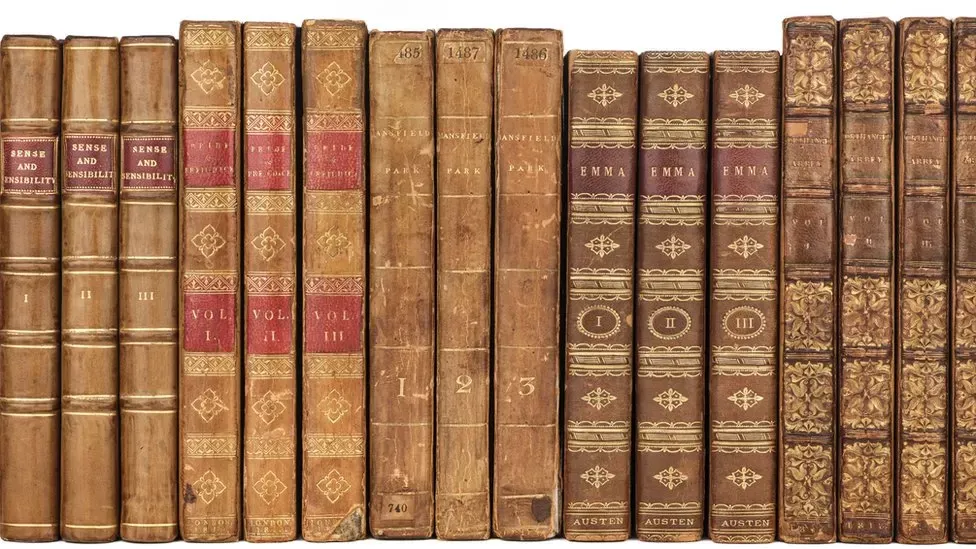

Austen recently had completed a revision of Northanger Abbey and now she was sketching out two new novels. The first, The Watsons, was frankly autobiographical, but eventually it would frustrate her and she abandoned it. The other, a parody of Gothic novels, expanded on some of the themes of her earlier work. This time she mischievously had Harris Bigg-Wither in mind. She would capture his moodiness and his awkwardness around women and yet enhance his appeal a little. He would be the master of the house but he would be unmarried, possessing a dark secret that would be revealed near the end of the book. Her heroine would be like Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, poor in riches but rich in imagination, a plain Jane. The hero, Mr. Bell, would propose to her and she would accept and then would come the bombshell that would blow it all apart. Perhaps the romantic couple would not end up together? Austen worked quietly away over the next few years, reshaping her encounter with Harris Bigg-Wither in a satiric direction, but she would not live to see it published. Indeed the manuscript, which was called Thornfield, disappeared in the next few years during one of her frequent travels around the south of England. She assumed it was lost or destroyed. In fact, her ailing father had lent it to a clergyman colleague who claimed to know a publisher. While her father was well-intentioned, the manuscript’s disappearance had only upset Jane. It would surface years later under another name but by then it was completely altered.

There were other matters on her mind, however, that pushed the lost manuscript from her mind. This had been a dangerous time for all of the family in the aftermath of the French Revolution and the onslaught of Bonaparte, and there were any number of political opportunists around arguing for revolutionary change. Even among Austen’s own circle, the events across the Channel cut close to home. Everyone knew someone who had been guillotined and for the Austens it was cousin Eliza de Feuillide, who had lost her husband to the guillotine in 1794, leaving her with an invalid child and little income. Every family in England had a son in the navy or the army keeping Bonaparte in check. What, in the end, was the value of a Revolution if everyone ended up in a worse situation than before? The Austens followed political events closely and everyone in the house read and discussed Edmund Burke passionately, but they read not only to endorse such views but to understand the times they lived in.

Even the role of women was changing along with the times. In the previous century, marriage had been more of a tragedy than a comedy. Austen never felt she had been presented with adequate choices: it was either get married or become a governess or a teacher. Failing that, she supposed she could have aspired upwards into high class prostitution, except she knew she didn’t have the body or the temperament or the background for it. She was the daughter of a clergyman after all. There was always music and the stage but for those you needed some talent and neither meant financial security. That left marriage which, to quote someone else, was a kind of death, the death of a woman’s individual worth. One could even literally die in childbirth. Though she believed that for the sake of peace and quiet in the home, wives should defer to their husbands, she did not believe they should be their slaves. The institution of marriage was essentially a materialistic arrangement and Love played barely any part in it. She resented the pressures, the expectations, the prejudices and the small-mindedness that came with it. This was something new: a sense that one need not marry at all in order to be happy. So she took long walks, traveled constantly and wrote and wrote and wrote.

What was also new, what gave her pride and pleasure, was the growing assertiveness of Englishwomen, who were starting their own quiet English Revolution. Intuitively, Austen had rejected Harris Bigg-Wither’s marriage proposal because she had always received enough emotional support from the company of other women, particularly her sister Cassandra, but also her mother and her friends. This gave her a freedom that was (or is) never understood or appreciated by those who turn up their noses at sisterhood and spinsterhood. This new freedom gave her the privacy she needed to write and it was her writing that gave her the emotional expression she felt she needed. Who needs a husband for that? If she were married she would be expected to run a household, bear a dozen children and then raise them. She would have no privacy, no time to write and without a doubt no imagination left. It would have destroyed her. Because her father was a clergyman she had been luckier than most in having the advantages of a library, an important factor when women were otherwise disadvantaged by being prevented from studying at university, but it was the company of women that gave her a diverse group of characters on whom she could test her storylines and from whom she could derive a steady supply of raw material.

Even after she was published, Austen always considered her privacy to be paramount. For this reason she used the pseudonym “A Lady.” She was content to leave it to wealthy women to worry about publishing their letters and diaries under their own names if they dared (they usually opted to destroy them). But Austen did not have the appetite to cope with the hostility of her critics. There are always going to be those who have absolutely no idea what you are saying and who proceed to tell everyone in their reviews how they would have written the book. Austen suspected the real reason she upset so many of them was that she did not take the follies of her life and times seriously enough. Irony is indeed a much misunderstood writing style. She was also irritated by the ugly class snobbery where everyone and everything was rated for its value. Even women were rated purely in terms of their conjugal and maternal roles. It was the same viciousness directed against “spinsters.” Even the word itself conjured up visions of her spinning thread rather than writing, yet she also knew it was being a spinster that kept her mind sharp. It was being a spinster that validated her life experiences. It allowed her to be the spectator, the outsider looking in, and it amused her that the prevailing assumption was that she was only of value to society if she had children. Women with children seemed to be able to talk about nothing else and, in her own heart, Austen knew she was not fond of children. Indeed, her novels were her children.

“WHAT WOULD EMMA HAVE SAID?”

What would Emma have said? She would have said, “Reader, she did not marry him!” She would have said that Jane made the right choice this time, that marriage proposals are the most critical moments in Jane’s novels and that not everyone says yes the first time, for very good reason. In fact, Jane’s novels are about first impressions and second chances, the twin anchors that steadied her own short life.

Take Pride and Prejudice. Elizabeth Bennet discovers that first impressions can be misleading. She rejects her man, Darcy, when she wrongly judges his character. It is only later, when she realizes he is perfect for her, that she accepts his offer of marriage. For Emma, the moral of Elizabeth’s story, was that prejudging a potential lover allows pride and prejudice to get in the way. The fact is, we never know to whom we are truly suited until the decision is made and the deed is long done. Married couples can grow together or grow apart; it can go either way. The odds are about the same as gambling. Jane realized this when she accepted Harris’ offer but she decided her first impressions, of the match, if not of his character, were right. Her pride and prejudice asserted themselves during the night. Was she right to call it off? Emma thought so. Why marry for the wrong reasons? Of course, marriage to Harris may not have been so bad. Life takes us all in strange directions and who is to say that life with Harris would have been so suffocating? One of Jane’s other characters, Charlotte Lucas (whom hardly anyone saw again once she got married) accepted an offer very similar to the one Jane turned down and she didn’t change her mind. But then Charlotte was a practical girl; she understood that marriage was more important than the man. Obviously Jane felt differently.

Fanny Price of Mansfield Park turns Henry Crawford down flat, much to the surprise of her family. But Emma thought that was a smart move because Henry was infinitely unreliable. Fanny goes on to marry someone else for love – the clergyman Edmund Bertram – and she gets to live at Mansfield. Evidently Fanny knew what she was doing. If Jane never married, then it’s fair to say that unlike Fanny, she never found a man who was smart enough for her. Certainly Harris did not match up. Emma considered this a significant point. Many women choose not to marry although they have their chances. Some, once divorced, do not remarry. Why do they hold back, despite the pressure they undoubtedly feel? Is it really for lack of choices? It isn’t because they are cynical about men (which they are) and it isn’t about sex. It has more to do with a desire to remain solitary because the life of the mind can be satisfied in other ways. It involves a choice – an honorable choice. It means protecting oneself from the messy entanglements of love and romance, which can take up far too much time and energy.

Emma herself was interested in those messy entanglements, of course, and she ended up marrying for love. She had that second chance after failing in all her own marriage-making. She was no fool though: “A woman is not to marry a man merely because she is asked, or because he is attached to her... It is always incomprehensible to a man that a woman should ever refuse an offer of marriage. A man always imagines a woman to be ready for anybody who asks her.” Was that what Harris Bigg-Wither was thinking when he proposed to Jane? Did he think she should have been grateful for his offer of marriage and accepted it?

Persuasion is the great novel of second chances, the second chances that Jane herself would never have. Its principal character Anne Elliott was 27 when her former lover, Captain Wentworth, returned. Seven years earlier, Anne’s family had dissuaded her from marrying him because he had no fortune. She was desperately in love with him, but she was overruled. Elopement was not an option. When he returned the second time, with a fortune in hand, her family were relieved to put aside their visions of Anne in spinsterhood and so the lovers were reconciled. The money no longer really mattered. Emma felt a twinge of jealousy because Anne was the first of Jane’s heroines not to accept a marriage proposal based on property. Anne is introduced to a couple, the Crofts, whose great marriage is based on mutual friendship and respect, not on rigid social roles that humiliated women. Jane may have felt the same way about her parents’ apparently successful marriage. But she could never have settled for a marriage that was defined by a set of principles she thought was obsolete.

Emma was no intellectual but she could see that their world was undergoing radical changes. Those genteel country houses and villages they had grown up in were being overrun by the modern industrial age, with factories, roads, canals encircling them and dividing them. Emma could see that traditional marriage values were being overrun in much the same way. If all Jane’s heroines ended up married by the end of their books, then it was also true that many women did not, including Jane herself, and even in the novels, Jane could not guarantee that her characters’ marriages were going to work out anyway. Was marriage really that essential? Leave it to the Romantics that followed Jane Austen to abolish irony and agonize instead over the personal crises of their central characters rather than whether they ought to get married.

Emma knew instinctively that Jane knew what she was doing when she rejected Harris Bigg-Wither that morning in 1802. For Emma knew that Jane did not need to marry him. She would come to terms with remaining a spinster, even if at times it made her feel like burning the house down. There were times though when she wondered about her lost manuscript from that unsettled time in her life between 1802 and 1805, when Harris proposed to her and when she lost her Gothic novel about the young Jane Eyre.