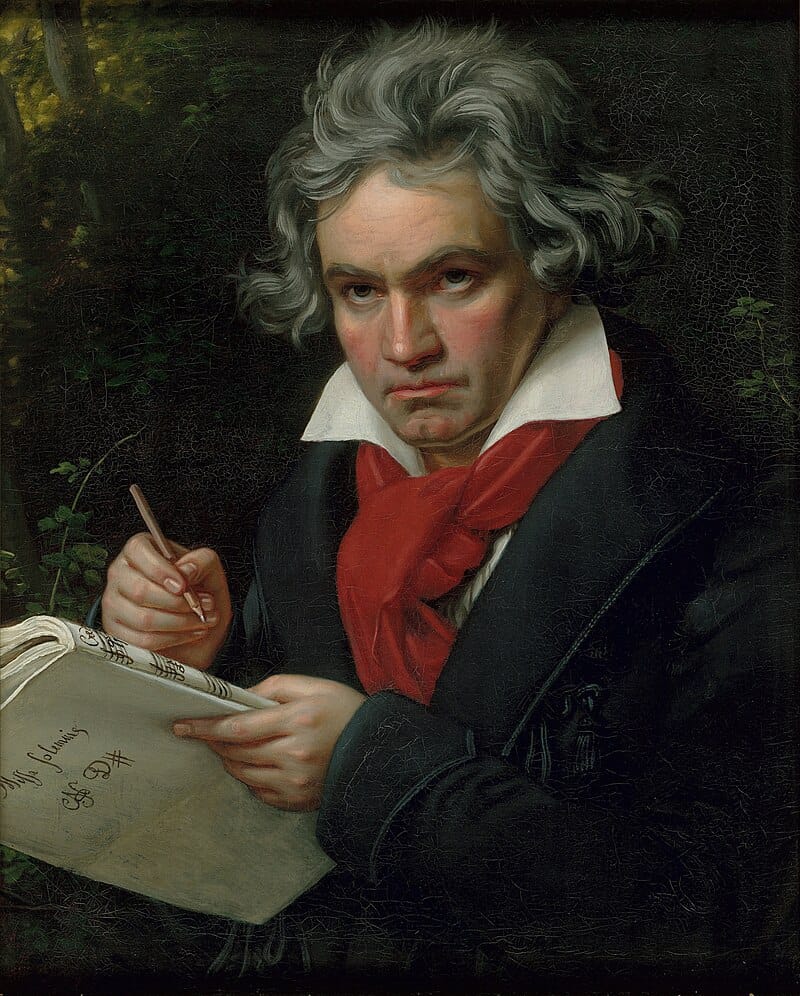

Immortal Beloved

Beethoven’s Love Letters

Beethoven's Love Letters

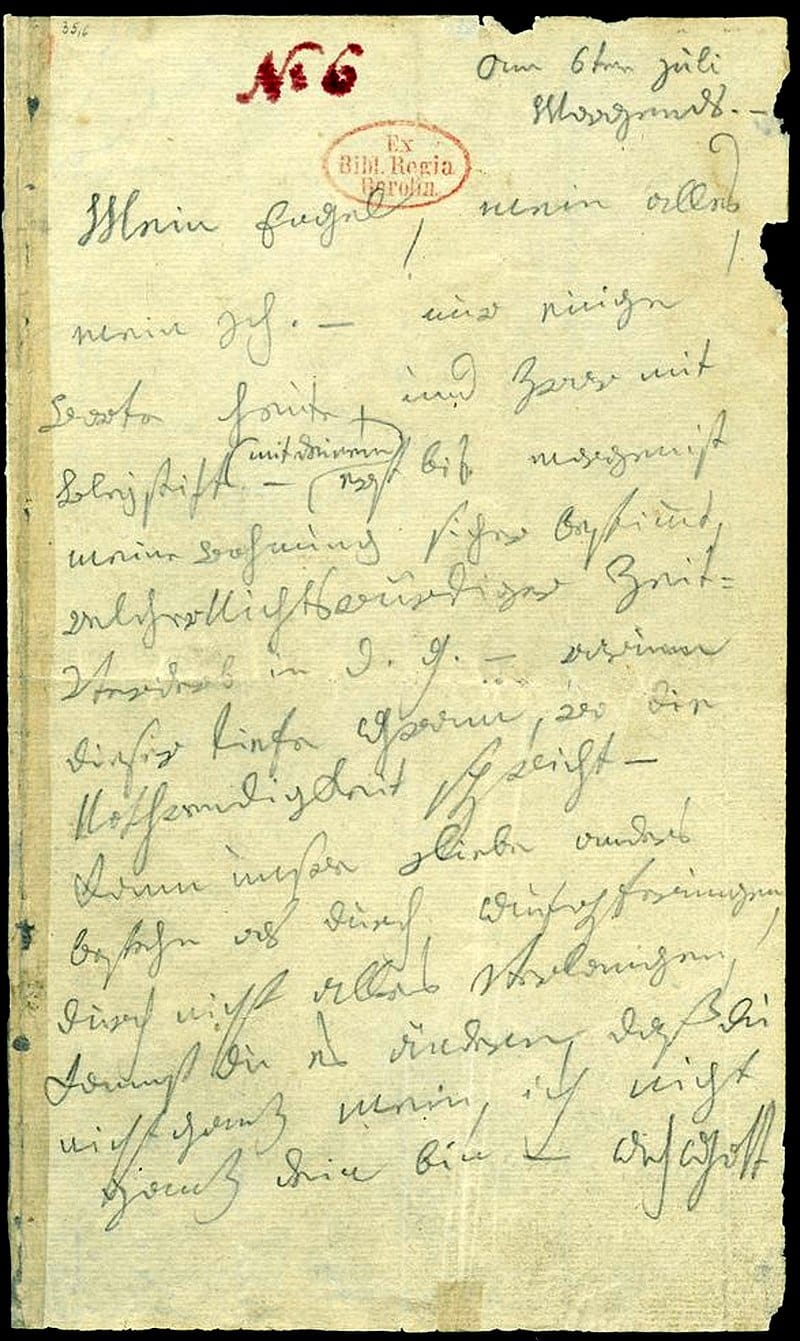

Once upon a time in old Vienna, the great composer Ludwig von Beethoven passed away quietly at his home. Back then, in 1827, his friends were going through his drawers when they found three letters tucked away in a hiding place. They were addressed to his “Immortal Beloved” (“unsterbliche Geliebte” in German, which some prefer to translate as “Eternal Beloved”). So began a mystery that has never been solved. Who was the mystery woman? Elsewhere in Europe, things were relatively quiet, with the Battle of Navarino over; George III, Napoleon and Byron were dead; Goethe was now 78, and people still believed in True Love.

There is no doubt they are real letters, using the customary flowery language of the time, and we know Beethoven wrote other love letters. There is some question as to whether these ones were actually sent. Perhaps he had second thoughts? Why else would letters end up back in his possession? In the 19th century, love letters could be returned to their authors once a liaison was terminated.

There are only two clues to go on. The first is that one of the letters is dated Monday, 6 July, and there were three years when 6 July fell upon a Monday: 1801, 1807 and 1812. The most favored year is 1812. The second clue is the mention of a town beginning with the letter K and, although we know Beethoven’s whereabouts with some accuracy for many periods of his life, there is ambiguity surrounding the three years mentioned above. Is it to a woman visiting Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic), in which case the hotel records for those years can be checked, or is it some other town near Vienna beginning with K such as Klosterneuberg, or Korompa (now Dolná Krupá, Slovakia)?

The letters may not be the great masterpieces of romantic writing that some Beethoven scholars have made them out to be, but they suggest he was a good writer with a keen awareness of when to employ romantic hyperbole without falling into cliché. They also have generated a controversy that has obsessed dozens of writers. This includes clever forgers who enjoyed writing their own letters, misdirecting earnest Beethoven scholars (in 1890 and 1911). They also have been made into a movie, Immortal Beloved (1994), starring Gary Oldman as Beethoven and they now have many websites devoted to them.

So who was this woman that he calls his Immortal Beloved? Some have argued that she was a quick intense flirtation that went nowhere just as fast. Others feel that she must have been someone he saw often at a particular time in his life. They argue that we should focus instead on why the relationship did not last. After all, why does he use the German words for “eternal” and “faithful” if not to suggest a long-term relationship, or is this just poetic license for an ideal woman – his muse – who never existed in the flesh?

How old was he when he wrote them? Was he 31 and young at heart, infatuated perhaps, which would mean he wrote them in 1801? Or was he closer to 37 and in the midst of his most creative and fertile period, in the year 1807? Or was he on the other side of 40, in middle age with deafness now roaring and whistling in his ear, in 1812?

THE EARLY CANDIDATES

It was around 1800 when Beethoven produced his first symphony and became famous. He was 30-years-old. Various attractive young women entered his life as piano students and three of them are candidates for the Immortal Beloved in 1801: the Countess Julie ("Giulietta") Guicciardi, and Therese and Josephine Brunsvik, the two daughters of the Count of Brunsvik. A portrait of Giulietta was found with the three Immortal Beloved letters in the hidden drawer and there was a portrait of Therese on his wall. The candidates for 1807, and this date is the least likely of the three, include Josephine, and perhaps Therese, and another confidante, Countess Marie Erdödy, whom he may have met as early as 1802.

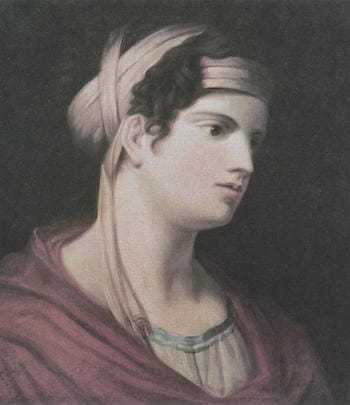

Giulietta Guicciardi

Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s biographer from his own era, thought that the Immortal Beloved was a young heartbreaker named Countess Giulietta Guicciardi who burst into Beethoven’s life in 1800 when she was 16 and he was 30. She had recently arrived from Italy with her family and she was young, sexy and vibrant. Greatly impressed with his musical genius, Giulietta did not mind his middling looks and general untidiness. One can speculate that Beethoven was not a good teacher; his head full of his own melodies. He cannot have been impressed with the playing abilities of his richer students, but then how did he deal with the allure of the young woman sitting before him. What must he have been thinking? Presumably music and erotic thoughts collided? Was marriage ever discussed? Since Beethoven had no title and no money, let alone what everyone perceived as his eccentric nature, her family would have objected to any match. Schindler feels Giulietta was no more than a coquette, an adventuress, like many young women at that age. She had a beautiful body, delicate features, great skill at flirtation and there was never any doubt that she could find herself a good husband. For that reason, she probably did not really want Beethoven and perhaps he knew it. A pleasant interlude did occur between the two at Korompa (a town beginning with the letter “K”), but she seems to have found it little more than a flirtation.

Beethoven’s relationship with Giulietta appeals to romantics. The beautiful Moonlight Sonata, which is dedicated to her, captures the spirit of their relationship: it sounds like moonlight on rippling waters. (This title was not Beethoven's but rather that of a music critic in the 1830s, but the name stuck.) Beethoven wrote to his friend Wegeler in November 1801: “You can scarcely believe how desolate, how sad my life has been for two years; my defective hearing has haunted me like a specter and I have fled from people, have had to appear a misanthrope when I am so little like one. This change has been wrought in me by an adorable, enchanting maiden who loves me, and whom I love; again after two years there are happy moments, and for the first time I feel that marriage could make me happy. Unfortunately she is not of my station in life.” Does this refer to Giulietta? What comes through in his writings from this time is the collision between his musical ambitions and his love for women, and music must always come first: “For me there is no greater pleasure than to practice and to display my art.” Though women stimulated and inspired his music, they could also drive him to distraction. Women were to be both his muse and his tormentor.

The onset of his deafness is crucial. After his break with Giulietta, he went on to write the traumatic letter of 1802 known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, named after a village northwest of Vienna that has now been swallowed up by the city. This last will and testament lays out Beethoven’s thoughts about his deafness and whether it meant he could find transcendence through music. This seems to be consistent with his beliefs in freedom, musically as well as politically. Freedom from class oppression, freedom from the old musical tyrannies, and freedom from infatuations with women perhaps. At any rate, he emerges stronger for it, and he never marries: “Had I chosen to give up my vitality to this love, what would have remained for that which is noble, better?”

Giulietta married Count Gallenberg in November of 1803 and they left Vienna for Italy. The Count was also a musician, though clearly not of Beethoven’s caliber and it seems the marriage was not a particularly happy one. Beethoven then plunged into one of his greatest symphonies, the “Eroica” 3rd Symphony, and perhaps we have Giulietta to thank for that, as much as we have to thankNapoleon Bonaparte. Years later, in 1822, he did meet Giulietta again when she returned to Vienna and he recalled the encounter in a letter of 1823 in this way: “She loved me, and even more than her husband... He was, however, more her lover than I...”

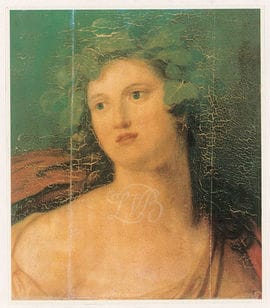

Therese and Josephine von Brunsvik

Schindler’s biography of Beethoven was published in 1860 and he actually knew Beethoven. But scholarship moved on after he championed Giulietta. A second influential biographer, Alexander Wheelock Thayer, published various volumes of his own Beethoven biography between 1866 and 1908, and in those volumes he favored Therese (“Tesi”) von Brunsvik. If we were to choose music for her, one critic has nominated Für Elise on the grounds that a copyist misread Elise for Therese and because the score was found later in her possession. However, Therese would be dropped from favor after her letters were discovered and published in 1946, indicating that she probably never loved Beethoven, though they had corresponded for years. She called him a “good human being,” which was probably true, but these are not the words of a lover. She never married. (There would be another Therese - Therese Malfatti - see below...)

A better case can be made for her sister, the Countess Josephine (“Pepi”) von Brunsvik. We are not talking here about a quick and intense infatuation like Giulietta, but a deep and lasting commitment between two lonely souls. The best evidence is the testimony of her sister, Therese, who wrote in her diary in 1860 that the Immortal Beloved letters “must have been addressed to Josephine whom he loved passionately.” Most Beethoven biographers agree.

Beethoven first met Josephine in 1800 but her mother married her off that year to the 50-year old Count von Dehm. It was not a happy arrangement. For one thing, he hated music, and the young Josephine must have found consolation and inspiration in her lessons with Beethoven. Fortunately for her, the Count died in 1804 and many believe that for several years after this, Beethoven and Josephine were close. Beethoven spent much of the summer of 1806 at the Brunsvik’s country estate of Martonvásár, 18 miles from Budapest. There he deepened his relationship with Josephine but there is no evidence of anything more than affection in her letters. It was an enchanting spot: the woods along the lake, the old world clothing and leisurely rhythms of life, far from the hustle of Vienna. If we have to choose a piece of music to capture Josephine, why not the idyllic Pastoral Symphony, no matter that it is dedicated to someone else and that inspiration may have come from the Helenental. Whether because Beethoven did not really intend to marry, or because of pressure from her family, or because she wanted a real father for her four children, Josephine von Brunsvik and Beethoven never consummated the relationship and they stopped corresponding regularly after 1805. He may have tried again in 1807, and certainly the years 1807 through 1809 were Beethoven’s happiest years, but there is no further evidence to go on.

Josephine married again in 1810 and again this was not a happy marriage. Her husband got into financial difficulties almost immediately, placing great strain on the relationship and he left her in June of 1812, the very time when most scholars believe the Immortal Beloved letters were written. It helps explain why Beethoven continued to take an interest in Josephine’s affairs and she in his. Her unmarried sister, Therese, looked after Josephine’s children during this time, while Josephine remained in Vienna, and in 1813 Josephine gave birth to another child. Evidently she slept with someone else and some say Beethoven was the father. Other biographers vehemently reject this. Whatever the truth of this, it points to a strong bond that persisted over the years, making her an excellent candidate.

THE LATER CANDIDATES

The earlier Beethoven biographers were perhaps over-keen to defend their hero’s honor but there are other candidates who could just as easily fit the bill: the Countess Marie Erdödy in 1807 and 1812 and Therese Malfatti, Amalie Sebald and Dorothea von Ertmann in 1812. And then there was his sister-in-law. Of course the lists do not stop there: there was Bettina Brentano who introduced him to Goethe that year and Magdalena Willman, a young singer from Bonn. It is perfectly feasible that he was in love with more than one woman in 1812. Within seven years Beethoven would be totally deaf and he remained a bachelor throughout his life. When he died in Vienna in 1827 he was aged 57.

The Countess Marie Erdödy

Erdödy owned the estate of Jedlesee, on the east side of the Danube in what is now a northern Vienna suburb. Beethoven first turned to her after his disappointment with Giulietta Giucciardi, and he spent much of his time there over the next few years. The Countess would have been 27 in 1807, by which time she had been separated from her husband for 6 years, and Beethoven was 37. It seems like a good match. In 1808, arguably his best year, the Countess was allowing him to entertain friends at her house, hosting concerts and genuinely relaxing. Couldn’t his happiest years have been in the company of the Countess? Certainly this is the view of Beethoven’s women biographers, Dana Steichen (Beethoven’s Beloved, published in 1959), and Gail S. Altman (Man of His Word, 1996) and a prominent Immortal Beloved website. Beethoven and Erdödy remained friends for many years, but she is regarded as the most mysterious of Beethoven’s women – we just don’t know enough about her. Beethoven dedicated his trio in D Major, The Ghost (Opus 70), to her, which is only appropriate for it has the ghosts of Macbeth about it. Erdödy would be expelled from Austria in 1823 during one of Metternich’s crackdowns on the Hungarians and she lived in Munich until her death in 1837.

In 1811 or 1812, Beethoven met Therese Malfatti, the daughter of one of his doctors. She may have been about 18-years-old and it is possible that he proposed to her but her family turned him down. We know he wrote at least one warm letter to her: “Commend me to the good will of your father, your mother, although I can yet lay no rightful claim to it... Now farewell, honored T., I wish you everything that is good and beautiful in life. Keep me in remembrance, and fondly -- forget that wild behavior -- be convinced that no one can wish you a freer, happier life than I, even though you take no interest... in your most devoted servant and friend, Beethoven.” She left the country soon after and married someone else, in 1816. Hardly any chemistry there, it would seem, but he must have tried it on with her, with all that “wild behavior.”

Then there was Amalie Sebald, a talented singer from Berlin who was 24 in 1812 when Beethoven was 42. He had met her the previous year in Teplitz (now Teplice, Czech Republic), another spa town, and there are seven letters Beethoven wrote to her in which he makes excuses for being sick. The relationship seems superficial and directionless. She calls him a tyrant in one letter; not a good sign. A similar case can be made against Dorothea von Ertmann.

It seems more than likely that the Immortal Beloved was already married. Could she be the woman referred to in this letter of March 1816 to his friend and student, Ferdinand Ries: “All good wishes to your wife; alas, I have none; I found but one woman, and her I shall never possess, but that has not made me a woman-hater.” Put all this together and the portrait of Beethoven that emerges is of a crusty old man who chased younger women in a feckless awkward way that he knew was doomed to fail, but that his real love was a married woman.

Johanna Reiss

Ludwig von Beethoven would have been perfect material for Sigmund Freud. Some of Freud’s successors, the psychoanalysts, came to the conclusion that there was really no Unknown Woman. Dr. Richard Sterba, a colleague of Freud in their Vienna days before the Second World War, and his wife Edith, gave much thought to this mystery. They produced a book, Beethoven’s Nephew, in 1954, in which they offer a psychoanalytic account highly critical of Beethoven’s behavior. They point out that after the death of his brother Karl, Beethoven fought the widow, Johanna Reiss, in the law courts for guardianship of his nephew, and that he nearly drove his nephew to suicide (in the Helenental in 1826). For a time, the Sterbas even considered the idea that Karl’s wife, Johanna, was in fact the Immortal Beloved.

Building their case, the Sterbas also argued that not only was Beethoven’s deafness caused by the physical abuse inflicted on him by his own father, but that Beethoven’s own vicious cruelty toward Johanna and his obsessive control over his nephew can only be explained by the fact that Beethoven and Johanna had an illicit liaison that fell apart in Karlsbad at the time the Immortal Beloved letters were written (she was there too?). The Sterbas’ bombshell is that his nephew was actually their son! It was this theory that would become the thesis of the Hollywood film of 1994. There is, however, little evidence to support it, but it is certainly colorful. Beethoven goes to extreme lengths to criticize Johanna’s “pernicious tendencies.” “She tried to infect everyone, even the most innocent people, with her moral poison (and...) her hellish yet stupid activities.” What supports the Sterbas’ case is that Johanna actually named her daughter (by another man) Ludovica, which is the female form of Ludwig. It would seem that Johanna was a powerful and proud woman, every bit the match for Beethoven. Some biographers -- Solomon for example -- defend her fierce love for her son, suggesting that it was her stout resistance that brought an out-of-control Beethoven back to an even keel. For Johanna, why not “Ode to Joy” from the Ninth Symphony, for while its musical roots lie in Beethoven’s earlier years, this also accords with the fact that he was long acquainted with his sister-in-law.

But was Johanna also the Immortal Beloved? In the course of their investigation the Sterbas concluded that the Beethoven who wrote those ugly words to “Circe” probably never sent the Immortal Beloved letters.

RECENT THEORIES

Antonie Brentano and Princess Almerie von Esterhazy

In all this wild speculation there is a surprising absence of good detective work and literary analysis, compensated for by lots of wishful thinking. Indeed it wasn’t until Maynard Solomon’s influential 1977 biography of Beethoven that we were able to get information about the stagecoach passenger lists, hotel logs and police records of July 1812. Lo and behold, a new candidate emerged: Antonie Brentano.

Antonie, who was born in Vienna, had returned to live there in 1809. She met Beethoven and they became friends. She was also married with four children, frequently in ill health and unhappy in her marriage. Solomon details how the letters to the Immortal Beloved refer to a rendezvous in Karlsbad, Bohemia, and everything seems to fit, including reports of the weather at the time, the initials used to refer to people, and other documents. It is an ingenious explanation, undermined only by the fact that apparently none of Beethoven’s contemporaries noticed the relationship under their very noses. In recent years, a similar case has been made by Jaroslav Celada for Princess Almerie von Esterhazy; originally proposed in 1960, it has now been translated into English.

While it cannot be automatically assumed that Beethoven was referring to Karlsbad, psychologically both candidates ring true. The letters are fascinating if read as the end of a relationship and this would be appropriate when we consider that he retained these letters in a hidden place. Was it the make or break moment in the relationship? Was Antonie prepared to leave her husband? Did he rebuff her when he realized that this was indeed what she intended? Was he hoping Princess Almerie would marry him, despite the long odds? Would marriage interfere with his freedom to compose? Did he feel his deafness, irascibility and bachelor habits made him a bad choice for a husband? Whatever the reason, the first letter to the Immortal Beloved emphasizes words like “necessity” and the “sacrifices” that each must make, especially her. It seems like Beethoven is discouraging the Immortal Beloved from expecting too much from their affair. Is he rationalizing the impending failure of the relationship? He goes on at length about his difficulties traveling through the forest but seems to be truly on his mind are the difficulties posed by their relationship. He is presenting himself as the busy man of affairs, the Famous Composer, and Goethe and other famous men gave similar reasons for avoiding marriage. Still, it sounds like an excuse. His expressed desire to live together just does not ring true. The first letter ends with the underwhelming “Your faithful Ludwig” and the last letter ends like a brush off: “Farewell.” Is he setting impossible terms? Is he being insincere or simply resigned? It is the letter of a man who wants to keep a woman interested in him, attached to him, yet he apparently does not want the woman to want more from him because he does not think it can last.

But does he then regret his words, even try to reverse them? After all, he doesn’t want to lose her, though he senses that may be coming. He knows she is hurt by his indecisiveness, his coolness. The Immortal Beloved letters are the only ones where Beethoven uses the more intimate form “Du” rather than “Sie” when writing to a woman. He is trying to maintain the relationship through his declaration of intimacy. He wants to persuade her that their love can still embrace these separations and vexations. But he is contradictory because he is imposing most of these on her. One minute he wants his freedom, the next he is wishing they can be together. The letter reads like the romantic hyperbole of the heroic genre, as if he would rather that the friendship could stay the way it is. No wonder it didn’t work out. He would irritate any reader, whoever she was.

The relationship was over by September. Antonie, who had become pregnant again (in June), would leave Vienna with her husband in November, as all the women in his life would do. Beethoven’s romantic aspirations were never the same again after that, and the stories of his infatuations with women diminished from this time, as he slid forever into middle age. Solomon argues that all these rejections by the women in his life had a “cumulatively devastating effect” on Beethoven’s pride, eroding his manhood. This is way over the top and it spoils an otherwise excellent book. Another biographer argues the opposite and that Brentano's son Karl Josef was Beethoven’s child...

This did take its toll on Beethoven. There is a diary entry in 1812 on the subject: “Submission, the most devout submission to your fate, only this can give you the (self-) sacrifice – for your obligation. O hard struggle!... You must not be a man, not for yourself, only for others. For you there is no more happiness except in yourself, in your art. – O God, give me the strength to conquer myself; nothing must chain me to life. In this way with A. everything goes to ruin.” Whether the “A.” is indeed Antonie (it is not clearly an “A’), the important thing here is that Beethoven is feeling rueful after another relationship, perhaps his most intense yet, has gone adrift, but he is rationalizing this as the price he has to pay for his composing.

Some years later, he would dedicate the Diabelli Variations (opus 120) to Antonie - it was written in Mödling, near Vienna, where he frequented his favorite pub, The Three Ravens.

LETTERS TO UNKNOWN WOMEN

Beethoven remains an enigmatic figure who has escaped all his biographers. Goethe, who met him in 1812, referred to him as “an utterly untamed personality.” In many ways the man who emerges in the pages of his biographers is a patronizing stereotype, where his character is sacrificed to his musical genius or to tortured psychoanalytical explanations of his love life or to bourgeois ideas about untidy bachelorhood and constantly revolving apartments. But individuals often display a consistency between their musical beliefs, their political beliefs and the way they behave toward the other sex and this is apparent throughout his career.

At 22, he was excited by the French Revolution: the spirit of change was in the air and it comes through strongly in his music. The storminess and sense of romantic melancholy mark it off as profoundly different from Mozart, who had died in Vienna the year before Beethoven got there. During these years -- the 1790s -- many considered him pretentious and arrogant, even if his closest friends were fond of him. But his instincts were accurate: the world was changing dramatically and he felt like Faust struggling against an adversary that could not yet be identified.

The psychoanalysts concede that Beethoven was a Romantic. They know he was much impressed with Goethe’s masterpiece of German romanticism, The Sorrows of Young Werther. The hero of that novel had been driven to suicide by his futile love for a young woman whom he has idolized. Similarly the heroine of Beethoven’s one opera, Fidelio: Married Love (1805), is Leonore, who disguises herself and breaks into the prison where her husband is kept. She rescues him and in the process exposes the tyrant who is responsible for imprisoning him. It isn’t just a tale set against the Terror in Paris; it is also an expression of Beethoven’s desire to be rescued by an extraordinary woman. Such an idealized Woman is common enough in every generation of men, and it seems that Beethoven was prepared to believe in Her.

But Beethoven also had a puritanical side that prevented him from forming any real-world attachments; he claimed to a friend that he could never have composed Don Giovanni or The Marriage of Figaro because they were too “wanton.” Several biographers claim he made use of the services of prostitutes from time to time, which in turn led to the charge that he contracted gonorrhea. In fairness, this is a charge others have denied, saying that he was fascinated by prostitutes, but he never slept with them.

Could Beethoven ever have married? Was he in fact happier imagining idealized women rather than marrying real ones, always in love with someone, but too clumsy to win her? Perhaps he was only interested in women he couldn’t have? We have here the classic fortress mentality, an obsession with moral purity, an ongoing sexual conflict between desire and fear, with the inevitable self-punishment that follows. In many ways, he fits the description of a perennial bachelor, unable or unwilling to form a lasting relationship. Certainly, many women found him unattractive and too eccentric. He couldn’t flirt, he couldn’t dance, he was not a great dresser. Sometimes he resorted to an awkward ear trumpet. This would have made him nervous about marriage, especially when he found himself bellowing at beautiful and desirable young women.

But Beethoven was exciting too and there were many women throughout his life who adored him. His musical genius and his passion made him attractive, in a wild kind of way, to many women, and he liked their company. In fact, he was a man who preferred women’s company over men’s and they were vital in stimulating his musical composition. As one friend later commented, “He was frequently in love... but generally only for a short period.” He may have never wanted to proceed past the point of intense flirtation anyway. He wanted more from life than to be locked into a set relationship and he lived life hard until he encountered the next woman who would engage him and inspire him, always aware of the risk this entailed, for he could become obsessed, as anyone can be.

All agree that Beethoven often behaved badly with married women and that there were other women that he took an irrational dislike to. He thought both his brothers had made bad marriage choices. Yet as anyone who has been in divorce court can testify, the legal battles with Johanna Reiss don’t seem that out of the ordinary once one allows for the intensity of the emotions involved. The vicious methods employed to get one’s way, from outright lying to involving high powered lawyers and influential friends, are still around today. In later years he would rail against Metternich’s police-state, but he was left alone by the secret police because he was deemed too famous and eccentric to be a real threat.

Too often ignored in all the biographies, however, is that Beethoven also had a hearty laugh – he could enjoy life when he wanted to and this sense of joy is captured in his best music. This is more revealing than all the pages about his awkwardness and his eccentricities. At the end of the day, the mystery of the Beethoven Immortal Beloved letters is equally interesting for what it says about us: our desire to solve amorous mysteries that pique our curiosity, especially as they might reveal how famous men and women truly feel about their lovers and their spouses and the sense of lost opportunities that are always implied. It is the idea that mysteries like these frustrate and fascinate the biographers and historians, for they are of course the same people who shudder at supermarket checkouts when they see contemporary scandals and mysteries exposed in the tabloids (“Sensational discoveries at Beethoven Mansion. Did he have a secret lover? Beethoven has love child”).