Women in Trousers

Pope Joan and The Rose of Versailles

POPE JOAN

Once upon a time there was once a Pope named Joan. Even the Vatican accepted for centuries that John VIII, who was Pope from 855 to 858, may have been a woman.

According to the medieval folklorists, the truth was revealed when she went into labor during a religious procession through Rome and spilled her baby on to the hard stone streets. Depending on whom you want to believe, the only woman Pope and her baby died during this traumatic childbirth and were buried on the spot, forcing subsequent Popes to detour around it. Symbolism is important. Others say that she survived the birth and was stoned to death for her sacrilegious behavior and was buried some time later; there is no word on what happened to the child. Then there are those who say that she was locked up while her child was spirited away to be the Antichrist of the Last Days.

Like all good stories this one spread wildly. The centuries rolled by and it turned out that she was an Englishwoman born to missionary parents in a town near Mainz, Germany. While a teenager, so they said, she had met a handsome young monk at the nearby Benedictine monastery of Fulda and they had fallen madly in love. Shamefully, she abandoned her parents and went and lived with him, dressed as a man of course since that was the only way to stay in the monastery. When things became too hot, they eloped to England and thence to France where she picked up an easy doctorate. Some years later they went on to Italy, ending up in Athens where her lover took ill and died. Joan by now was very learned in church doctrine and possibly superior to all the men, so she went to Rome and opened a religious school. It wasn’t long before she was elected Pope.

So was it history or folklore? In the 15th century the existence of Pope Joan was an accepted fact. The great Italian Renaissance writers Boccaccio and Petrarch, who knew a good story when they heard one, were very fond of it, for it had the right ingredients to appeal to the medieval imagination. Church moralists saw in it a deceitful woman who was unmasked by her own body, for a woman’s body was a holy shrine, was it not, and how could she desecrate it in this way, by having sexual relations and getting pregnant?

Those of a more secular nature responded to its sheer extravagance. In the 16th century, Protestant writers picked it up because it was perfect for annoying the Catholic Church. They pointed out, not unfairly, that if Pope Joan had got herself pregnant to one of her monks at the Vatican then it was probably a cardinal, or possibly it could have been the Devil himself? Pope Clement VIII tried to kill the story in 1601 but it wouldn’t go away. French writer Stendhal took a look at it, as did Lawrence Durrell last century.

Pope Joan has her defenders of course: she appears in an awful British film of 1972, Pope Joan, starring Liv Ullmann, and ex-billionaire Malcolm Forbes was so entranced by her that he included her in his 1990 book, Women Who Made a Difference. Donna Woolfolk Cross’ novel, Pope Joan, sold very well and it became the basis for a German feature film released in 2009.

Women who masquerade as men have always held a fascination, of course, since they were as rare as men who masqueraded as women. But, now that Trans identities are widespread and dynamic, past examples of women in trousers are more interesting. How could the Pope Joan legend have been so wildly successful and for so long? Was it just the religious times those writers lived in? Religious folklore exercised an enormous influence on western European thought from the early medieval period until the Enlightenment. However, Joan has disappeared from the official Catholic list of popes; the Church has banished the one female pope from existence. Fortunately, every 10 years or so a new book comes out in French or Italian, and occasionally in English, speculating about why the legend caught on as it did. These books argue that back in the 9th and 10th centuries, the male authorities feared powerful religious women. They certainly did not want them meddling in church politics – let the sinful behavior of Pope Joan be a lesson to you, they declared.

Nowadays, sadly, Joan belongs to the historians who are mostly Cynics: if it isn’t true, dissect it and dispose of it as feminist and anti-Catholic propaganda. But there are those who see in her story a triumph of ingenuity whereby a woman fooled the men and made it to the top of the Catholic Church which suppressed her story out of fear of Women’s Power. These are the Optimists. Then there are those who would see in it a gruesome disaster whereby the men got rid of her in the most bloody and painful way. These are the Pessimists. Finally, there are those who have never believed or disbelieved the story per se but who take pleasure in it as a rip-roaring story that leaves room for the imagination. These are the Agnostics. Even today they are looking at new ways to work it into that Hollywood movie. Think of the fictional possibilities of the child becoming the Antichrist: was it a boy or a girl, and who was it that who turned up in Linda Blair’s body in the The Exorcist?

Everyone responds to story-telling through one of these categories – the Optimist, the Pessimist, the Cynic and the Agnostic – whenever they read a book or watch a play or see a film. As my daughter would say, they match Hufflepuff, Slytherin, Ravenclaw and Gryffindor maybe? Human nature being what it is, individuals consistently favor one of the four over the others. Which one is you?

Perhaps there is a resemblance here to the classical theory of humors, whereby Hippocrates and Galen divided human natures into Sanguine, Melancholic, Choleric and Phlegmatic, or Air, Water, Fire, Earth? In the 21st digital century, we may render it as (+ - 0 1). It shares a resemblance to ancient Daoist notions (yang and yin, qi or ch’i and the absence of qi), and the Japanese interest in blood types (O, A, B, AB).

SEXUAL FABLES

Sexual fables like “Pope Joan” are pleasurable because inevitably they end up as sensational scandals, and today’s scandals are little different from those of the past. The criminal courts and congressional hearings may have replaced the Inquisition and the heresy and treason trials of the classical and medieval eras. Nowadays it is Bill and Monica, OJ Simpson, Michael Jackson, Woody Allen versus Dylan Farrow, Donald Trump versus...well, everyone. But their scandals are really the familiar moral tales that people have created in every generation, sometimes horrific, sometimes laughable, and they can move us at a deeper level than traditional highbrow literature.

For there is always more here than meets the eye. Sexual fables present us with enigmas that crystallize the sex and violence that otherwise have been banished (canceled) from everyday life by the politeness police. They come across as surprisingly abstract and complex and while they usually have instantly recognizable characters, those characters are involved in strangely murky deeds. Audiences have found themselves situated on diametrically opposite sides. Indeed, what drives the great sexual fables is exactly this ability to polarize viewpoints and to render it difficult for anyone to arrive at a final judgment, however tempting that is. The best sexual fables do not take sides because we are all sitting under the Rashōmon Gate.

Pope Joan may hold little interest for people today, for very few seem to care about literature or the arts or history. Perhaps that is a good thing, for if everybody did care, we would live in an impossible world of poets and dreamers. But for those who do care, the experience of traveling through time and space to ask how such an extravagant story arose in the first place is to experience human connectedness. To pick up a book about Pope Joan or to browse her on the Web is time/space traveling, back to the Renaissance and beyond. It can suggest that things were not what we thought. It can ask, for example, Could there have been any female popes? Even if there weren’t, was it possible for a woman to have done what Pope Joan did? Even if it wasn’t possible, isn’t it an entertaining idea that she might have been able to pull it off? In the end it doesn’t matter whether there was a Pope Joan or not, but it matters a lot that we enjoy the idea that it might have happened.

VITA SACKVILLE-WEST AND 'ORLANDO'

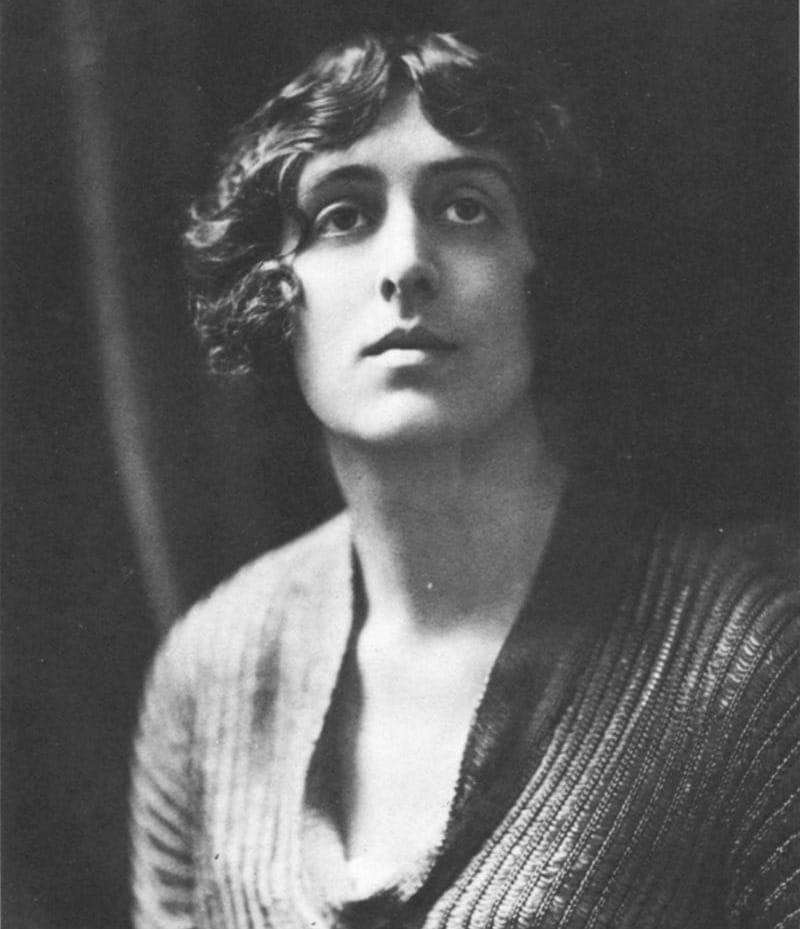

A great many other women have run around in men’s trousers over the years, but few have been as interesting as English aristocrat Vita Sackville-West, who served as the inspiration for Virginia Woolf’s surprising novel of 1928, Orlando: A Biography.

Sackville-West was born rich and never really recovered from it, but she lived a far more fulfilling life than her Bloomsbury contemporaries. She was from one of those elite families that had helped build the British Empire, but who found themselves made redundant as the empire collapsed. Perhaps Tolkien had her in mind with the Sackville-Bagginses of The Lord of the Rings – the deliberate suggestion of cultured snobbery in splendid isolation? But instead of drifting off into self-pity and shattered spider webs as her twice-time lover of the 1920’s, Virginia Woolf, did, Vita Sackville-West got busy reinventing herself as a gardener and gardening writer! With her husband she purchased Sissinghurst Castle in Kent and they restored it, from 1930 onwards. It is now a tourist attraction, administered by Britain’s National Trust.

Sackville-West is proof that real-life stories are a lot more interesting than literary ones, for she outshines both Orlando and Virginia Woolf. She is certainly more interesting than the Bloomsbury Group, to which she never really belonged, and that is why there have been almost as many biographies and articles written about her as about Woolf and, until recently she was more widely read than Woolf, although Woolf was unquestionably the better writer. Vita, who was over six feet tall and looked great in a wide-brimmed hat and men’s clothes, was undoubtedly eccentric. But she always understood she was different and if lesbianism was a difficult lifestyle to lead at the time, then she made the best of it by marrying a bisexual man, having his children and carrying on her amorous affairs pretty much as she pleased. As did he. That happy marriage lasted almost 50 years.

The highlight for anyone reading her biography today is her very public affair with girlhood friend Violet Trefusis from 1918 through the early 1920s when they eloped to the south of France with their husbands in hot pursuit in a private plane. It was a moment of high comedy, like something out of Oscar Wilde: Vita dressed as a man and going under the name “Julian” and Violet as the femme. Such scandalous behavior made international headlines. Not that Vita didn’t need rescuing sooner or later, for Violet had their future lives together mapped out for all eternity, to the exclusion of husbands, children, friends, everything. Vita was too free a spirit to want to suffer that fate. She wrote about the affair in her novel Challenge (1923), but she set it on a Greek island and called her own character “Julian,” turning it into a heterosexual relationship. Nevertheless, it was still unpublishable in the England of the time. Vita’s and Violet’s parents saw to that.

If Vita played the masculine role, it is fair to say that like the rest of the Bloomsbury group, she was interested in androgyny. Not in a George Sand kind of way, for Sand was heterosexual and she played with gender stereotypes somewhat analytically, while Vita, like Woolf, would rather have blurred them altogether. Not in a Radclyffe-Hall kind of way either, for Hall was the openly masculine lesbian who wrote the scandalous 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness, which precipitated a trial about “sexual inversion.” Vita instead found herself somewhere in between masculine and feminine (“Florid, moustached, parakeet-colored,” sniffed Virginia), which is why Vita started a diary to try to figure out her “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” sexual identity swings. Her choice of literary metaphor is revealing.

Woolf wanted to figure her out too, which is why she wrote Orlando. In the novel and subsequent film, Orlando is born a man, becoming a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I. During the reign of Charles II, “he” becomes a woman and stays that way as three more centuries (and many more lovers) roll by. Early editions of the book had photographs of Vita in various costumes re-enacting parts of the story and, metaphorically, it would seem that Woolf identified something timeless and even mystical about Vita – certainly her energy and her strength, but also her ethereal androgynous qualities. In her turn, Vita writes about Virginia this way, “What an enchanting person Virginia is! How she weaves magic into life” -- and yet it is exactly this quality that Virginia envied about Vita – her magic, her unabashed lesbianism and her devotion to her husband. Woolf would end her life in 1941; Sackville-West would put her love into her garden at Sissinghurst until her death in 1962. If Orlando is a surreal portrait of Vita, a cross-dressing cross-over between fiction and non-fiction, a blurring of male-female boundaries that accurately summed up Vita’s life, then it’s also true that Vita’s life was more interesting than the Dorian Gray portrait that Woolf came up with. Woolf’s voices and the madness got her in the end, but Vita lived a full life, albeit in semi-solitary confinement, lost up the garden path somewhere.

Transition

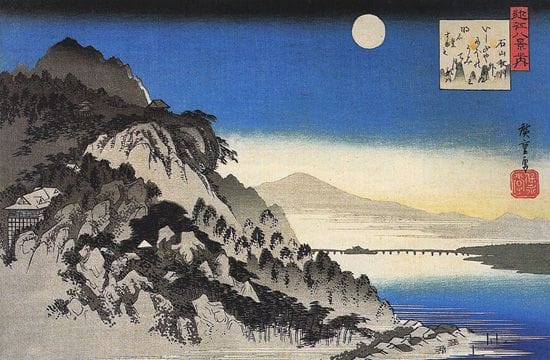

Vita Sackville-West would have made a great manga character. Japanese manga writers have had an unerring eye when it comes to Western literary and musical figures who might make a fine hero or heroine. The day will surely come when they discover Vita. Of course Vita showed no particular interest in Asia, but surely she met translator and critic Arthur Waley at some point since they both moved among the Bloomsbury Group. When Woolf published Orlando, in 1928, Waley had published his translation of Blue Trousers, the fourth volume of Murasaki Shikabu’s The Tale of Genji, arguably the finest classic Japanese work of literature ever written (circa 1000 AD) - the painting below reminds me of it. Vita could have been in those blue trousers. In Genji they are a mourning costume and Vita, resigned to growing older, did retire herself to Sissinghurst.

Perhaps there is something revealing about the Western figures who have had manga written about them: Ulysses, Jesus Christ, Joan of Arc, Catherine the Great, Beethoven, Ludwig II of Bavaria and more obscure figures like the gender-bending Le Chevalier D'Eon. They are all larger than life, figures of mystery, all worthy of sexual fables. But think of what they got in return: The Yellow Princess, Madame Butterfly, The Mikado and Memories of a Geisha.

'THE ROSE OF VERSAILLES' AND TAKARAZUKA

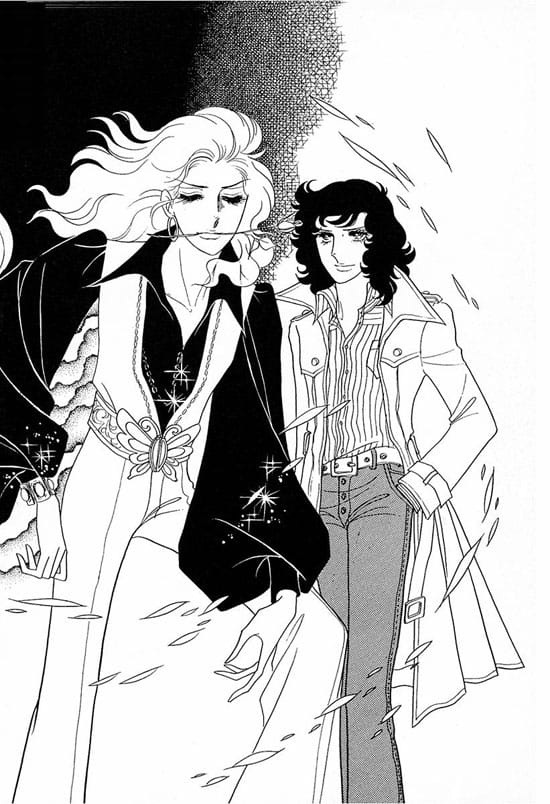

Many decades ago, a great manga was released in Japan that captured the spirit of Vita Sackville-West and Genji and it shaped an entire generation of women. You can’t mention “BeruBara” to Japanese women over the age of 50 without having an impact. The Rose of Versailles, as it is known in English, debuted in 1972-3 in Japan and it is still widely known there, and not only because the manga was so beloved. From 1974 onwards, it also became a trademark hit show of the all-female revue company Takarazuka, which is based near Osaka.

The Rose of Versailles helped define a new women’s genre of storytelling in Japan and it did this partly by idealizing feminized men – indeed they are so feminized you might think they were women. This is something Westerners are not familiar with at all and I can think of no comparative examples. Not only that, the main character of The Rose of Versailles literally is a woman, playing a man’s role: she is the Lady Oscar and “she” is the captain of the Queen’s French Guards in the era of Marie Antoinette, immediately before the bloodbath known as the French Revolution. Totally fanciful as this may seem, Lady Oscar (or Oscar Francois de Jarjayes), is dressed as a man in uniform and everyone knows “him” to be a woman.

Oscar is the youngest daughter of General Jarjayes, who raises her as a man, setting in motion a collapse of all the key differences between masculine and feminine into androgynous. A “bishonen” character like Oscar is a staple of manga and anime, where “beautiful young men” are immensely appealing to younger Japanese women readers and viewers and you can see them on Japanese streets today. This reflects a common characteristic throughout Asian art and literature, where beautiful young men are the objects of desire for both men and women, even though this is apparently an alien concept in the West. It also is part of a tradition: the most famous work of classic Japanese literature, The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari), has a bishonen main character and the female roles in Kabuki theater are considered bishonen. In the West, androgynous men and women seem to disturb the fundamental order of things (and of course many artists have capitalized on it – David Bowie and Madonna for example). However, bishonen tends to refer to men and the Lady Oscar is a woman, which is creator Riyoko Ikeda’s unique twist.

The Rose of Versailles (Berusaiyu no bara in Japanese) went on to become an anime series and anime fans today laugh along with it, as if it were some quaint relic from the closet. After all, there are over-the-top displays of trickling tears, rose petals blowing in the wind, leaping horses and sparkling fireflies. However, that does not mean it isn’t held in high regard. The sense of rage that was there in the 1970’s is still there for those who want to see it, the story races along and the political analysis is shrewd, given that we are talking here about a shôjo manga, entertainment for teenage girls.

The Rose of Versailles was emblematic of an era, capturing a strong desire by Japanese women to throw off patriarchal restraints. Not that it ends happily… The Lady Oscar is a sacrificial figure whose love for her friend Andre is destroyed by reactionary forces as much as by TB. There is much made of crucifixion imagery (or Disney’s Sleeping Beauty if you prefer) and there are strong echoes of the warrior maiden Joan of Arc and her execution at Rouen. The message is clear: loving is suffering and Japan, not France, has to change the way it thinks of its women. For women, it says that standing by one’s lover is more important than meekly accepting what society thinks is appropriate: “Not realizing one’s love is more sinful than betraying one’s love” runs one line. There is also a subtler message of course: we all die and “The Seine still runs…”

The Rose of Versailles also went on to become the most successful stage production ever mounted by the Takarazuka dance company. This all-women company apparently means very little in the West, and again this is surprising. Since women play the men’s roles as well, a fascinating androgynous type has emerged at Takarazuka – the male “otokoyaku” (“musumeyaku” perform the female roles). All this acting out has encouraged speculation by Western feminists that lesbianism is the sub-text of such Takarazuka performances and its enormous female fan base. But, this has always struck me as dead wrong. This is not to say that some of the performers and audience aren’t lesbians, but the vast majority aren’t, and I’m not even sure I buy the counter-argument that it’s all “asexual.” Indeed it is very sexualized, but in a way that crosses genders in a fluid way that suggests that Japanese women are attracted to this display of gender-bending in a deeply emotional way rather than a purely sexual way, something more akin to flirting and role-playing.

That sort of thing does not fly in the U.S… A romance like The Rose of Versailles blurs m/f and f/f and m/m via androgyny, but groundbreaking romances like Will & Grace, The L Word, Queer Eye and Brokeback Mountain, and the shows that followed, while they also drew in primarily women viewers, and they have some kissing, they rarely relied on androgyny – men play men and women play women. Also, the Japanese seem to have more fun with it, while in the U.S. it has become a totally serious business, where we are constantly reminded that we are looking at two men or two women. It has only been in the Twenties that the Trans movement and shows like Euphoria have made androgyny more acceptable and just look at the backlash! In the U.S., apparently we never want to be confused about which one we are looking at, and the neurotics are king (or queen). It is my sense that many TV viewers miss the campiness and cheerfulness of the old comics and TV shows where, if sexuality was repressed, then no one seemed too angst-ridden or woke about it (TV’s Batman or the Superman comics for example). Of course they never noticed it either…

Romance is one thing; hardcore is another. If women in Japan find romance between two men (m/m) appealing, very few seem to find the equivalent hardcore version appealing. They apparently prefer men and women having sex (m/f) and women having sex (f/f), but mostly they are repelled by men doing it (m/m). It is the same in the United States. Or perhaps I don’t know the right women? Why is it acceptable in romance but not in hardcore? The answer seems to be that women can find a place for themselves in the romantic action but they feel shut out by hardcore, and the same appears to be true for hetero men, in both the West and Japan, where they like m/f and f/f hardcore but not the m/m.

'BROTHER, DEAR BROTHER'

Before moving on to yaoi, it is worth a quick look at Riyoko Ikeda’s other ground-breaking manga, Oniisama e (Brother, Dear Brother). It came out (so to speak) around 1975 and in it the roles are reversed and it is quite frank in its interest in GL (“Girl Love”), or yuri or femslash. While yuri traditionally does very well with lesbians and males, how does it do with heterosexual women? Fairly well, it would seem. While many manga and anime, like Takarazuka, have female leads in romantic, even erotic situations, they are not really lesbian fantasies, whatever Westerners think of them. Brother Dear Brother, on the other hand, crosses that line decisively (in fairness, it's rather more complex than this sounds). Set in an expensive all-girls school that reminded me at the time of a deranged Takarazuka revue, or perhaps American McGee’s Alice slashed with Beauty & the Beast, it has several lesbian relationships and pretty much everyone has obsessions of one sort or another – swooning crushes, drugs, cruelty, knife throwing, suicide – all set against the familiar backdrop of roses, clock towers, frilly dolls and long slender fingers.

The story is told by Misonoo Nanako but the main figures of interest are its seemingly lesbian and androgynous figures (and I say "seemingly" because the plot whipsaws our expectations around quite a bit). These figures include Nanako's friend Shinobu Mariko and three older girls. The first is Orihara Kaoru (Kaoru no Kimi) who is a tomboyish type nicknamed after a Prince ("Kimi") in The Tale of Genji and she has a dark secret. The second is Asaka Rei (Hana no Saint-Juste), nicknamed after the French revolutionary figure Louis de Saint-Just, who looks like the Lady Oscar and who is bent on self-destruction. The third is Fukiko Ichinomiya, the rich and vindictive student president, whose nickname Miya-sama ("Princess") evokes The Mikado.

This fascinating manga and the anime deserve to be a lot more famous than they are but it is virtually impossible to find them anymore (I bought the anime from Technogirls, but the shorter and more surreal manga was harder to track down). The anime was shown on NHK in 1991-92, when Japanese media were markedly sympathetic to gay issues, and it was around this time that Sailor Moon debuted, and that went on to become the most well known manga and anime with “out” lesbian characters. But Brother, Dear Brother is far more interesting -- more ambiguous, more Gothic, more emotional and more moving. It’s hard to imagine U.S. media ever producing anything like it, ever...

YAOI AND FUJOSHI

Back in the 1970’s, The Rose of Versailles signaled a new frankness among a generation of Japanese women who enjoyed romantic scenes between what really amounted to two men, since Lady Oscar might as well be a man. But it has evolved since then into a wide range of characters and eccentric behavior in all genres, including isekai fantasies, while remaining romantic at its core – Sailor Moon, Revolutionary Girl Utena, and so on. They have been very successful among young people in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere, and in fact they have been far more successful than home grown comics, but they have not caught on with young American women to the degree I would expect. Why not? “Chick lit” is more successful here and yet there is nothing risqué about chick lit; it is egotistical, neurotic and conventional by comparison with yaoi.

Yaoi or BL (“Boy love”) is still a uniquely Japanese phenomenon, for all the growth outside Japan of slash fiction, homegrown yaoi and yuri conventions. There are publishers in the U.S. trying to market yaoi to American women, but it looks to be a tough sell if for no other reason than young American women are by and large unaware of it. The sales figures in the U.S. for Gravitation and Fake were said to be encouraging (if they can be believed), but presumably it was the tamer editions that sold. It is the same elsewhere in the so-called West.

So, can yaoi (or BL) ever catch on here? Is it really just more women in trousers, “girls playing with dolls” as one manga critic alleged, or is it “pretty, sexy, and fun” as one of its defenders argues? Both probably…

The best analyses zero in on the aspect of “performance,” in other words the way that often these are really female actors playing fantasy male roles just like in Takarazuka – these “men” are really women playing men for female audiences. Sometimes characters find themselves switched from male to female. Still, this means that these manga are definitely heterosexual rather than homosexual and the fans invariably are women rather than gay men. These women find it appealing that they have freedom to identify with either side of the couple, which is not possible to the same degree in conventional m/f story-telling.

There are many people in the West who would be repelled by yaoi if they ever were to see it; they would consider such imagery pornographic. Conversely, some women might be turned on by it. But for most women it is fairly tame in the sense that it is essentially static images staring back at you from the page. It cannot compete with voyeuristic “adult” video footage that thrusts itself at you. Like romance novels with two guys, it is still the relationships and the story in yaoi that matter and even though some yaoi have become hotter and sweatier in recent years, it is still very feminine.

Does that mean that if Japanese women consume yaoi in great quantities then they are frustrated with the traditional distinctions between masculine and feminine, or that they don’t take them as seriously as women from other cultures? Romance novels and tabloids are still fairly ubiquitous around the world. I don’t think we could conclude that Japanese women are more sexually frustrated with their men than women from other cultures are, although a poll in the Yomiuri newspaper in 2005 argued just that (Seven out of 10 single Japanese women believe they can be perfectly happy remaining on their own). It would be racist if it weren’t a Japanese study, in which case it just becomes polemical and sexist. Conversely, I don’t think we can conclude that Japanese women have richer emotional lives than other women, or that Japanese culture is more pro-gay (or anti-gay) or less repressed (or more repressed) than Western cultures, because in the end all of these studies and polls and unsolicited opinions are inherently culturally biased.

But there is definitely something interesting going on here with yaoi. Mostly it has to do with women creating their own erotic manga and anime, fields that traditionally belonged to nerdy males. When yaoi emerged, its fan base at first were disparaged as fujoshi (literally "rotten girls") but, as all good movements do, they appropriated the term and proudly declare themselves fujoshi as a mark of pride. The business community took notice, as did their boyfriends!

So perhaps the only thing we can say is that Japanese culture is less neurotic about gender distinctions than the U.S., because in Japan they have other things to be neurotic about? It is a paradox perhaps: in Japan there is less confrontation over gay rights, yet their yaoi- and gay-themed manga is more accepted within mainstream culture.