Midvinterblot

Sweden’s most famous painting, Carl Larsson’s Midvinterblot (1915), created controversy by celebrating the sacrifice of a pagan Swedish king who died to save his people – an explicit act of seiðr. Its power, of course, was that it reminded everyone that Christ’s death was a sacrifice, echoing the scandalous arguments made by James Frazer in the recently published The Golden Bough and Viktor Rydberg before him.

The painting upset many of Larsson’s contemporaries because it seemed pretentious to imitate Christ. They didn't say so directly, of course. They objected to the rituals of pagan blood sacrifice as a throwback to a best-forgotten primitive era, refusing Larsson's point that both Christ's sacrifice and the king's sacrifice were connected to the physical world, to renewal of the species, which had been Frazer's point too.

The irony though is that there isn't any connection between blood sacrifice and fertility really, except what we have dreamed up. Sacrifice simply means death, not bountiful harvests. Not only that, Christ’s sacrifice (like Larsson's king) has eliminated the female principle. Fertility, after all, requires the fusion of male and female principles. This was an all-male affair, like the concept of the All-Father as progenitor and that's the trouble with spiritual concepts: although many conservative Christians would beg to differ, you can't get pregnant from an idea.

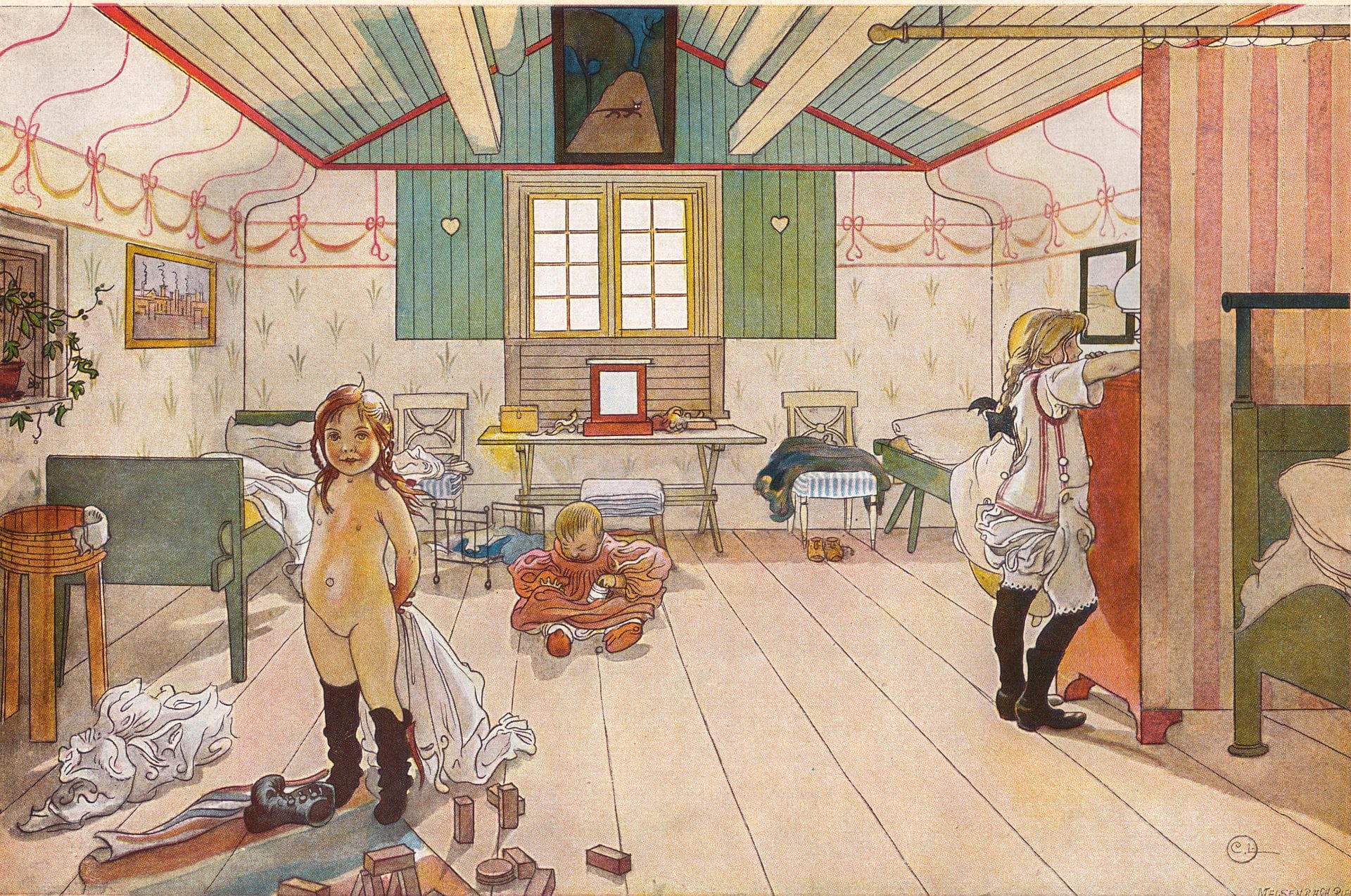

After many decades of controversy - and occasional exhibitions - the painting was finally installed where it was supposed to be installed in the first place (in Stockholm's Nationalmuseum) - in 1997. Below are two more Larsson paintings which point toward his relatively happy family life. I'm sure the upper one could drive censorious puritans into a rage, but Larsson was one of the most gifted painters of childhood ever...

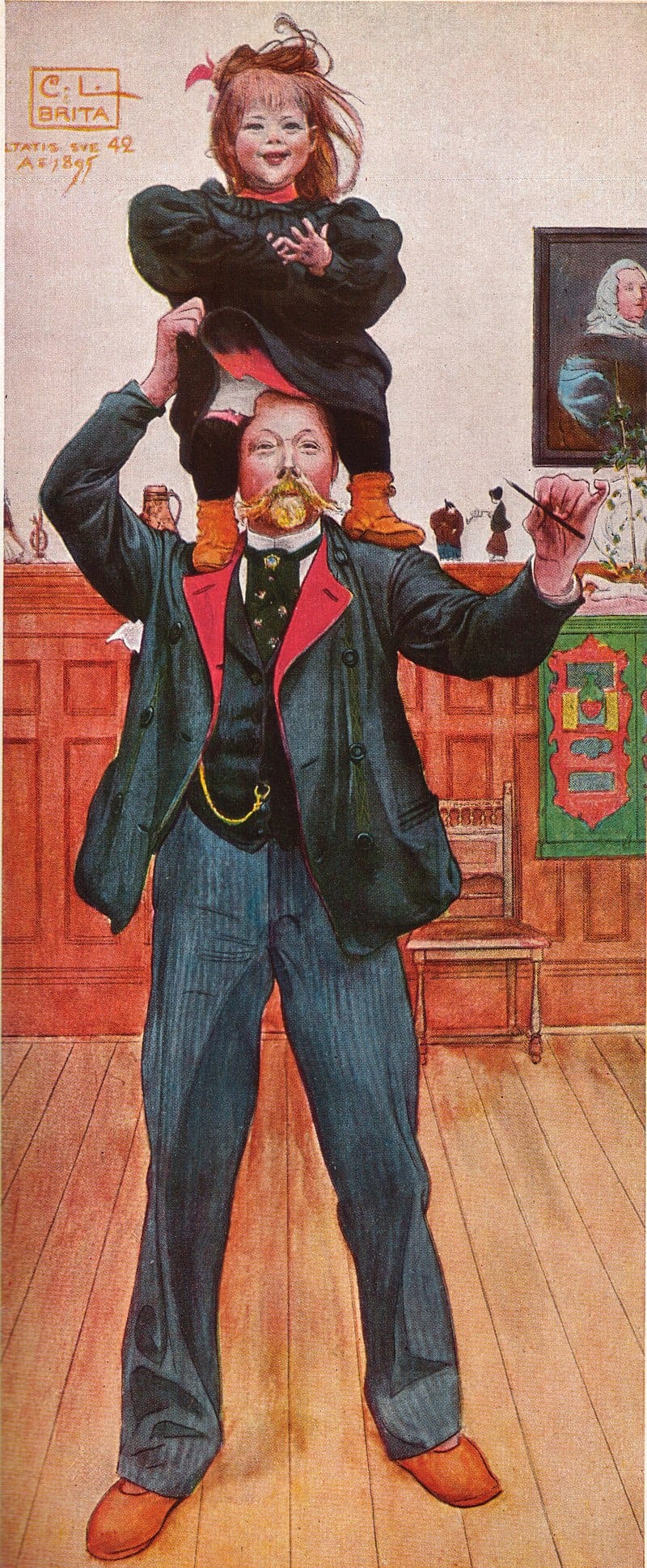

This one above is Mamma's and the Small Girls' Room (Mammas och småflickornas rum) from 1897. Below is Brita and Me (Brita och jag), a self-portrait from 1895 with one of his daughters.